When did you start your first job?

In 1819 there were no rules restricting the age at which a child could work. If a child was prepared to work and a mill-owner had a job they could do, they could legally be told to "start on Monday". The only limitations were those imposed by Robert Peel's Health and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802 but this only restricted the working day for apprentices aged under 21 to 12 hours and prohibited them from working at night. In any event, these rules were poorly enforced as there was no inspectorate to police them.

There was little question of school attendance. Compulsory education was still half a century in the future and while private schooling was available, fees had to be paid. Even the most basic of 'dame' schools would have cost a few pence a week; pence which the familise of mill-workers could ill afford. Indeed, the opposite was true, the small incomes of their children working in a mill might be the lifeline which kept the family financially afloat. The authorities too were unenthusiastic about educating the working classes. Reading and writing might expose them to seditious ideas (like securing the right to vote!) and facilitate them in organising to pursue these ideas; 1819 was, after all, to be the year of Peterloo.

The principle of children working would not have seemed strange to their parents. Those who had come to Manchester from rural backgrounds might previously have expected their children, as soon as they were able, to help around a farm or smallholding. This could involve feeding the chickens and collecting the eggs, scaring birds or simply fetching and carrying. Come harvest time, children worked alongside adults and we see an echo of this in the long summer school holiday, an acknowledgement, when compulsory education was introduced, that children in rural areas would not be in school during harvest time.

Parliamentary Investigation and the 1819 Act

Still, the healthy outdoor life of a farmer's child was a lot different to working a 72 hour week in the confines of a noisy and dangerous cotton mill. By 1815 parliament had started to recognise that this might not be the healthiest environment in which a child might grow up and in 1818 a parliamentary commission was appointed to examine the health of child workers in cotton mills. The major part of this investigation was to send medical examiners into a number of mills to examine the workers and to report on their ages and general health. Among the mills selected were those of McConnell & Kennedy, James Kennedy and Appleton, Ogden & Co. in Manchester.

McConnell & Kennedy's Mill [Mancheester Archives: Local Image Collection]

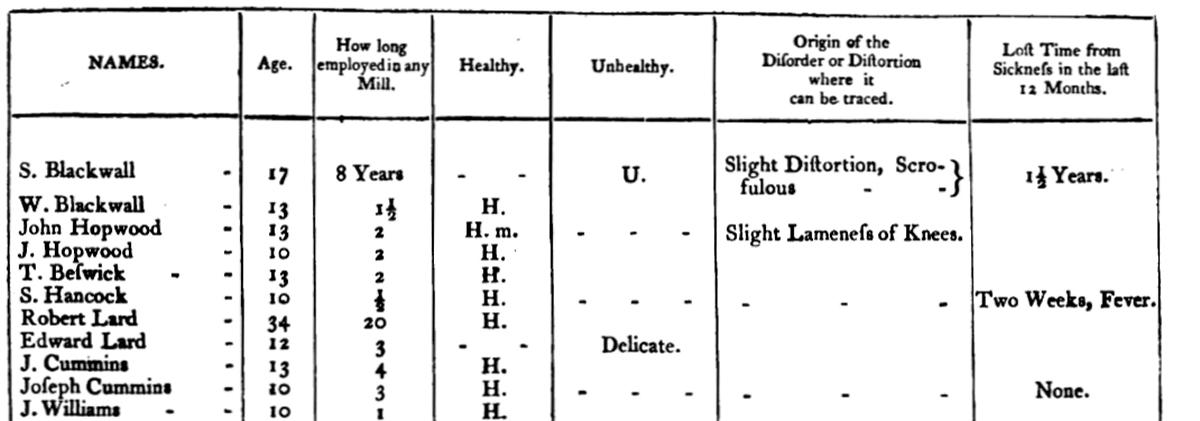

The details collected at the Appleton, Ogden & Co. mill give a picture of what the examiners found.

Their summary, which includes the surnames of the employees (though frustratingly only their initials and not their sex) lists 321 employees of which ages are given for all but 7 (who were absent, presumably sick, on the day of the inspection. Of these, 143 (45%) were aged under sixteen years. Of these 25 were under the age of ten, the youngest, H. Lee, being just seven.

The workers were also asked for how many years they had been employed in a cotton mill. Using this information we can determine that 284 (90%) had started work before the age of sixteen and 187 (59%) before the age of ten. 25 of these had started aged seven or younger. (These latter figures may be conservative; the question was "how long employed in any mill?" and for older workers there may have been a period of employment other than in a mill and so the age at which they started work may be younger than that calculated).

The health of the workers appears at first glance to have been surprisingly good. 270 (85%) were assessed as healthy and just 19 (6%) as unhealthy. The remaining 27 were assessed as "delicate". We have, though, no indication of how these assessments were determined. We can see that some of those assessed as "healthy" surrefed from conditions such as such as lameness, dyspepsia, persistent cough and scrofula (see below), so the bar does not seem to have been set particularly high. The description of children as "delicate" is also vague. It suggests, perhaps, a child who was thin and weakly (though clearly capable of working) but presumably not suffering from any specific complaint.

A sample from the Report for Appleton, Ogden & Co.

Six of those examined are noted as suffering from scrofula. This complaint, as unpleasant as it sounds, manifests as painless but often unsightly swellings of the lymph nodes in the neck and is caused in most cases by the bacterium mycobacterium tuberculosis and infection is more likely in those who are immuno-compromised, perhaps as a result of malnutrition. Several others are described as being "bow legged" or "in-kneed" (knock-kneed) and a few as having "distorted" legs. This suggests that they were suffering (or had suffered) from "rickets". This condition results from vitamin D deficiency, which in turn is linked to deficiencies in diet and lack of exposure to sunlight unsurprising when working indoors for most of the daylight hours). These complaints suggest that some of the workers were malnourished. Two children openly say that they do not get enough to eat.

The findings of the investigation led to new restrictions being introduced in 1819 in the form of the Cotton Mills and Factories Act. While an improvement over Peel's Act, these new restrictions did not greatly shift the dial. The major change was that it would no longer be permitted for children under the age of nine years to work in the mills. The other change, that those aged under sixteen years would not be permitted to work more than 12 hours a day, seems merely to be a re-stating of Peel's Act but with a lower age limit. The similarity to Peel's Act extends to the lack of any machinery for enforcement so it is arguable that little really changed on the ground.

Further Legislation

Further improvements followed through further Acts, but the first major change came in 1833 with the Factories Act (in full: An Act to regulate the labour of children and young persons in the mills and factories of the United Kingdom), which applied restrictions across all factories, and not just the cotton mills. This mandated a maximum working week of 48 hours for those aged nine to thirteen, limited to a maximum of nine hours per day and specified that children under thirteen years should receive two hours' schooling each day. Perhaps more importantly, an Inspectorate was established to enforce the rules. While initially only 4 inspectors were appointed, this gradually grew to become an effective body.

Several further Acts followed but it was not until 1901 that the employment of children under twelve years of age was finally prohibited.

Accessing the Records

The evidence presented to the 1819 House of Lords committee hearing can be found on Google Books.

The names of the persons employed in the McConnell & Kennedy mills, James Kennedy't mill and the Appleton, Ogden & Co. mill are indexed within the Great Database, available to MLFHS members.

- Hits: 148