I'm Reviewing the Situation

My 2x great grandmother, Mary Ann Leary, was born in Bermondsey about 1850. Like many children of immigrants born about this time there appears to have been no civil registration of her birth. And so, research has been slow and laborious. So, yes, legally her parents were supposed to register her birth and that of her siblings but like many they skipped that bit. However, even though she would not be recognised by the authorities, her parents did ensure she was baptised and thus would be recognised in the kingdom of heaven.

For many years I chased her elusive baptism plotting out all the Catholic churches along the Thames from Bermondsey and into Rotherhithe writing to each. I struck lucky and was able to finally obtain this information from a church administrator. Of course, had I only waited a few years I could have searched these online myself. Many catholic records are now obtainable online via at least two of the main pay per view genealogy websites, and in fact, I resurrected my Leary family search when MLFHS recently brought onboard the records from the now defunct Catholic Family History Society.

Consider Yourself

Mary Ann Leary, an Irish Cockney, has proved quite a tricky ancestor to trace. But after some recent success finding her death certificate and burial place with the assistance of a fellow family history researcher, I have redirected my search to try and determine her parents. By drawing up a spread sheet and literally trying to trace all the Mary Leary’s born about 1850 in or around Bermondsey. I have been going through each of these families one at a time. Of the eight possible Leary families I have been chasing, three had a father called Jeremiah! This task would have been made easier had I the details from the birth certificate but also if I could have found a marriage certificate for Mary Ann Leary to her husband James William Brown (that’s right, adding to my woes she became Mary Brown). But unfortunately, through the years I have been unable to discover these wonderful documents.

It’s a Fine Life

Alongside any life records I found (or not found!) during my search for various Leary family members like birth, Catholic baptisms, marriage, death, and census records, in particular it has been helpful to search out any social commentary. And this is where Dickens work has been so helpful.

Dickens actively sought out less respectable parts of London to explore and his written observations were based on what he saw in real life.

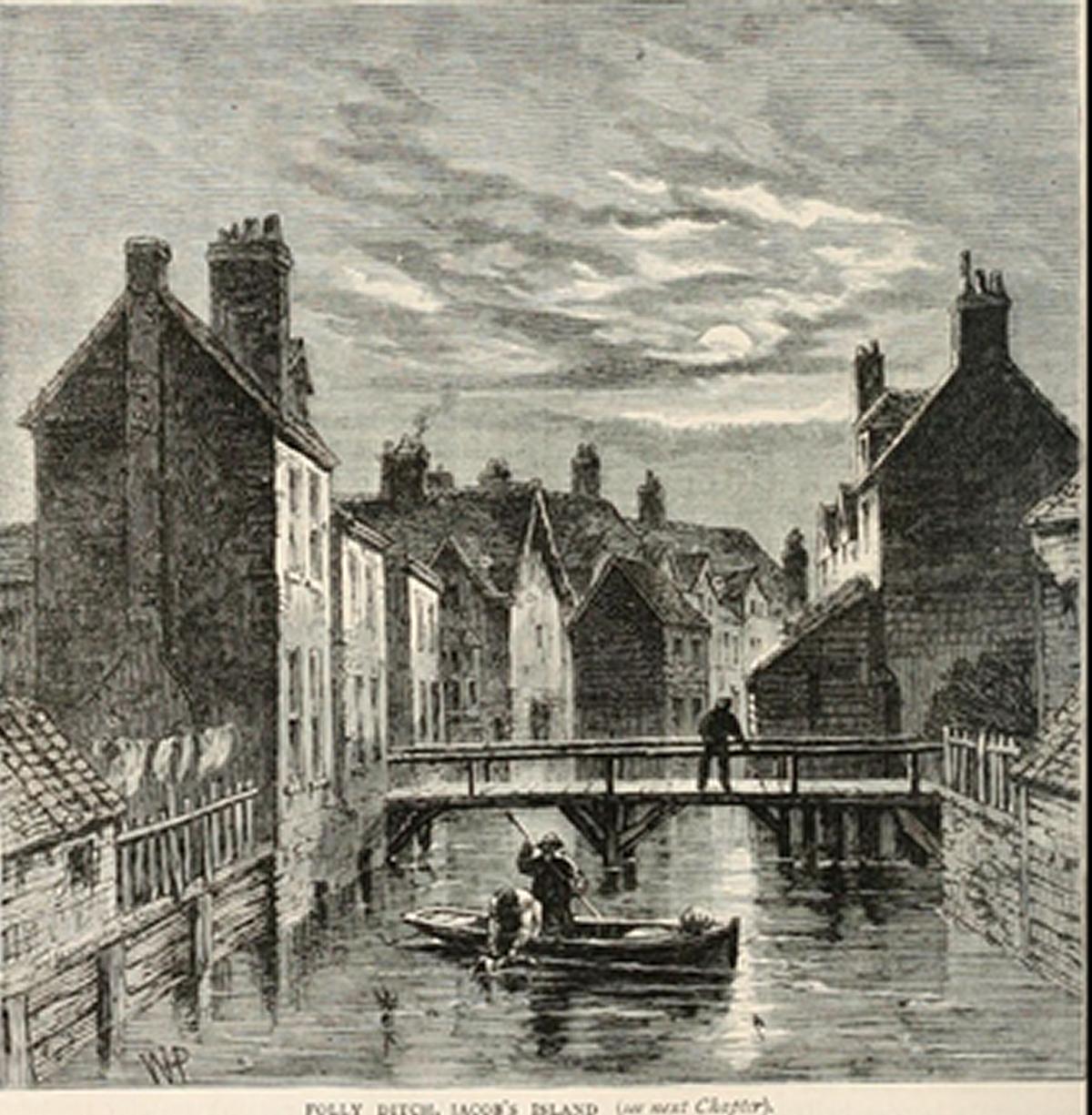

“A place named Jacobs Island was immortalised by Dickens in his novel Oliver Twist, in which the principal villain Bill Sykes dies in the mud of 'Folly Ditch'. Dickens provides a striking description of what it was like:

... crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem to be too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud and threatening to fall into it – as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage: all these ornament the banks of Folly Ditch”.

During my Leary research I realised that in 1851 my family were living in Hickmans Folley, which lay within the notorious slums of Jacobs Island .

Images Wiki Commons: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2b/Jacobs-island-00284-640.jpg

This slum was cleared in the 1860’s and I can now understand why my Leary family had moved elsewhere in Bermondsey by the next census.

A perfect resource to help introduce some social commentary into my research was Charles Booth’s London website. Which not only has a most wonderful interactive map of London but searchable notebooks of people and places. Booth was to spearhead an inquiry into the ‘Life and Labour of the People in London’. This was taken between 1886 and 1903. It was one of several surveys of working-class life carried out in the 19th century. We are lucky that the original notes and data have survived for Booth’s survey and it provides a unique look at London.

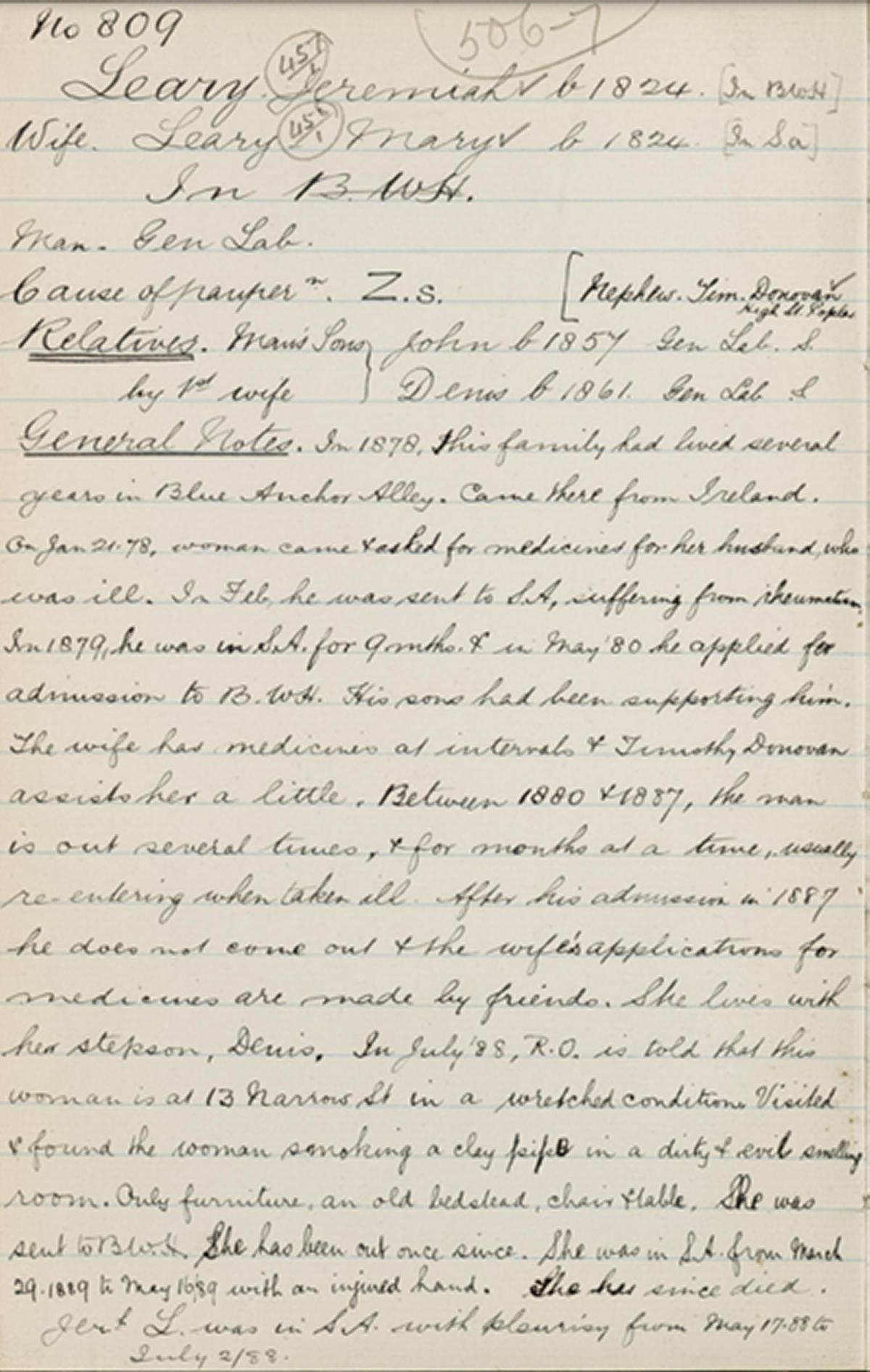

Below is a notebook entry about one of the Leary families that has been ‘ruled out’ of my search. The information found in one of the ‘poverty’ notebooks is bleak but very informative:

Inmates of Institutions Notebook: Stepney Union District 2: Particulars of Cases

Year: 1889 Booth/B/166 Public Domain

Here we learn that Jeremiah Leary was ill with rheumatism. He ended up in the workhouse, where he eventually died. Having searched for the family I can see the online workhouse records for Jeremiah during this period. Along with many other records which compliment this resource. However, it’s the additional details with are so telling. Toward the end of the page, we see that his wife Mary Leary is described during a visit ‘…is at 13 Narrow St in a wretched condition. Visited and found the woman smoking a clay pipe in a dirty and evil smelling room. Only furniture was an old bedstead, chair and table’. In the notebook entry, I’ve learnt about her family circumstances, names of family members and living conditions. It will, I’m sure be a ‘eureka’ moment for someone.

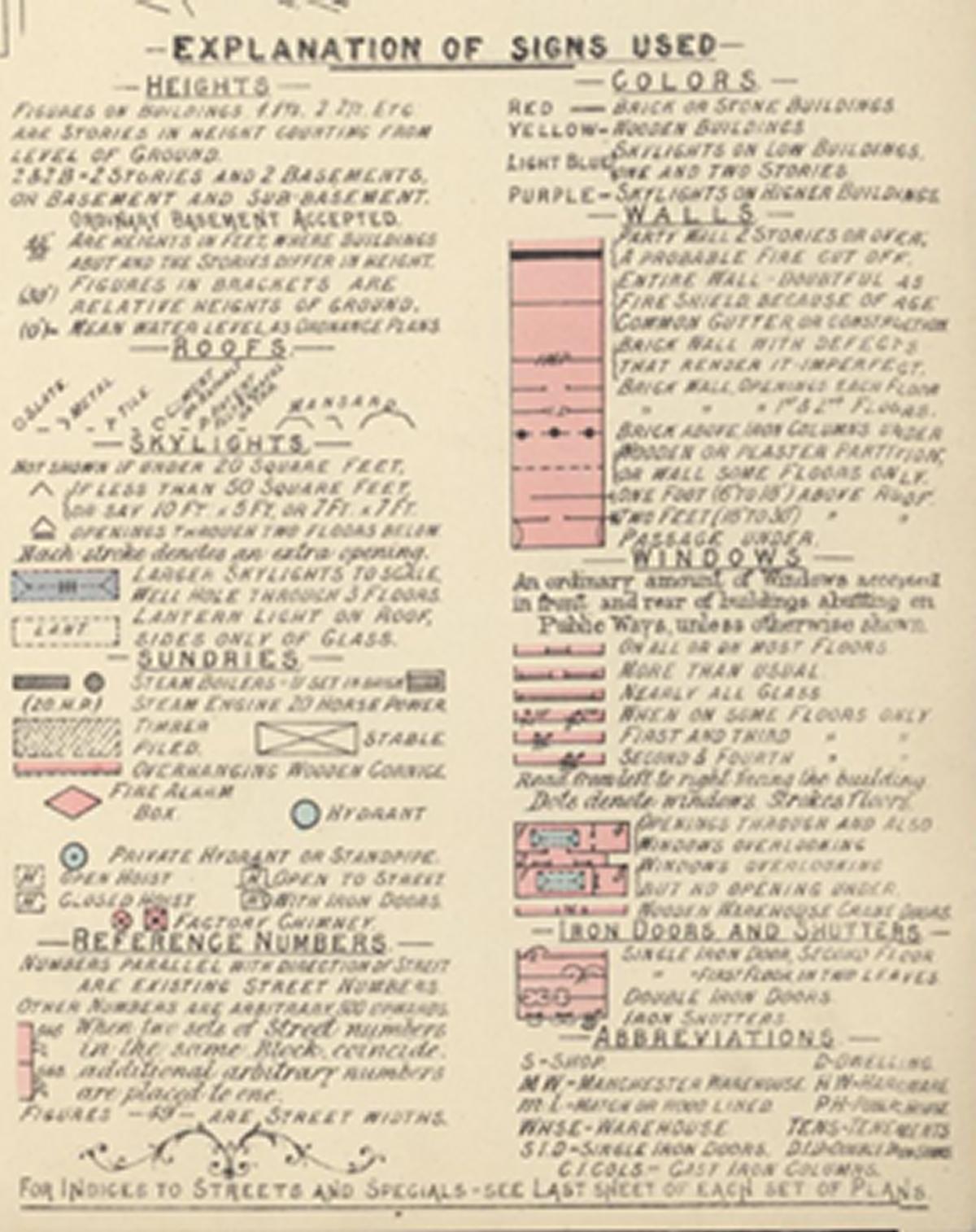

And, though not of great use to me on this occasion, another good source of information is the Charles Goad Fire Insurance maps of England which can be found on Wikipedia and for Scottish cities in the National Library of Scotland map collection. Charles Goad’s old street maps were created for insurance companies to underwrite the risk of urban fires. The plans focussed on commercial, warehousing and transport properties and facilities. Nicely drawn and very informative many including the type of building, the size of buildings, the materials employed in their construction, the use of each building, whether it was inhabited, the location of shared walls and outbuildings, the layout of streets, yards and alleys, and locations of fire departments and water supplies. For me, it has been so interesting just looking at the named factories and businesses, see where the churches and workhouses were located, and just the general street layout in and around Bermondsey.

Example of symbols used from a Charles Goad Fire map: https://maps.nls.uk/view/216810138.

And last but not least, a perennial favourite, the historic OS maps from the National Library of Scotland These have helped to guide me successfully around Victorian Bermondsey and Rotherhithe.

Be back soon!

Looking at such a variety of resources has certainly given me a better perspective on this family, particularly when it came to looking at addresses associated with census records. And, I might say some admiration for the census enumerators assigned this area! I feel this would have been a hard gig. Despite such a detailed search sometimes the answers just don’t come even after long hours of research. And although I’ve learnt a lot about many of the Leary families (spanning many years, the area of Bermondsey, and caught up on some Dickens, I’ve now come to an impasse. And so, for me it is important to know when to (temporarily) close up the research. I’m hopeful that some new data will eventually become available, and perhaps a sudden epiphany to try a different research method may pop into my head. But for the time being I will now need to turn the page on Mary Ann and the Leary family in Bermondsey.

“So long, fare thee well

Pip! Pip! Cheerio!

We'll be back soon”

- Hits: 59